Separating Architecture From Its Ethereal State

Creating new realities to escape our own has been part of our society’s reaction since the days of Plato and his Kallipolis. The world of speculative realities is, directly or indirectly, bound to architecture, becoming a parallel process designers employ to move forward when creating buildings. Yet, this discipline has often struggled to be recognised on its own and it has often been just an architectural pursuit.

For quite a long time speculation about utopias and our society has remained within the pages of books, but in the 60s, with the Futurist movement, a rejection for historical references and standardised ways to do architecture, in favour of forward-thinking designs and concepts, began. Notably, Archigram and Superstudio were amongst the studios actively pushing towards the idea of an architecture that does not need to be built, but rather that should provoke and challenge the way we think of design.

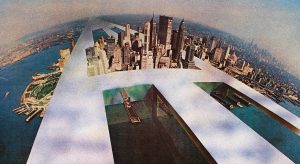

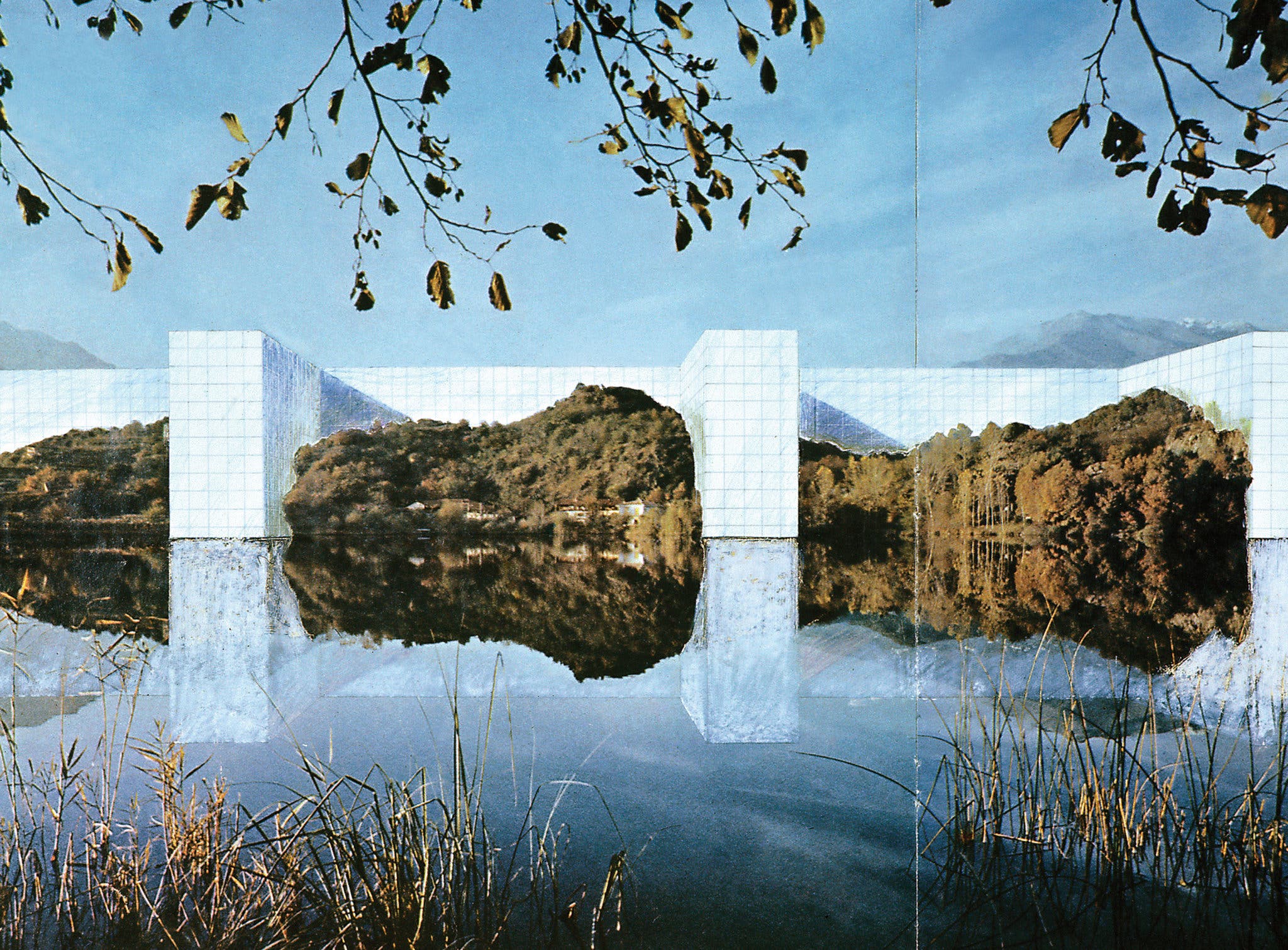

The Superstudio’s drawings for the “Continuous Monument”, depicting a piece of architecture that could stretch from one side of the world to the other with the purpose of unifying and ordering the earth, was one of the most incredible and memorable notions Speculative architecture witnessed. It was a provocation that touched upon numerous issues affecting urban realms in those years and it assisted in shaping how architecture developed back then. Collectives like Superstudio were crucial to uncover issues regarding our urbanism; they pushed the design world towards new ideas and their approach triggered a process of interest from various designers, leaving us to wonder the unexpressed potential their ideas would have had if not directed towards the design world only.

As speculative architect Liam Young says “The irony is that the industry that most rejects speculative architects is architecture. All the others are craving our skills. Speculative architects’ storytelling abilities combine temporal modes with spatial ones, and we are some of the only practitioners that are able to think in those terms.” Perhaps, this is where we should no longer look for, if Speculative design should not be buildable but remain ideal, therefore architecture is probably the most unfit discipline to nourish speculative ideas.

Provided that Speculative architecture and its graphic and narrative production serve as an escape from our realm to reimagine and subvert the concept we have of living, then they should be accessible to a large audience, in order to promote and advance its conversation.

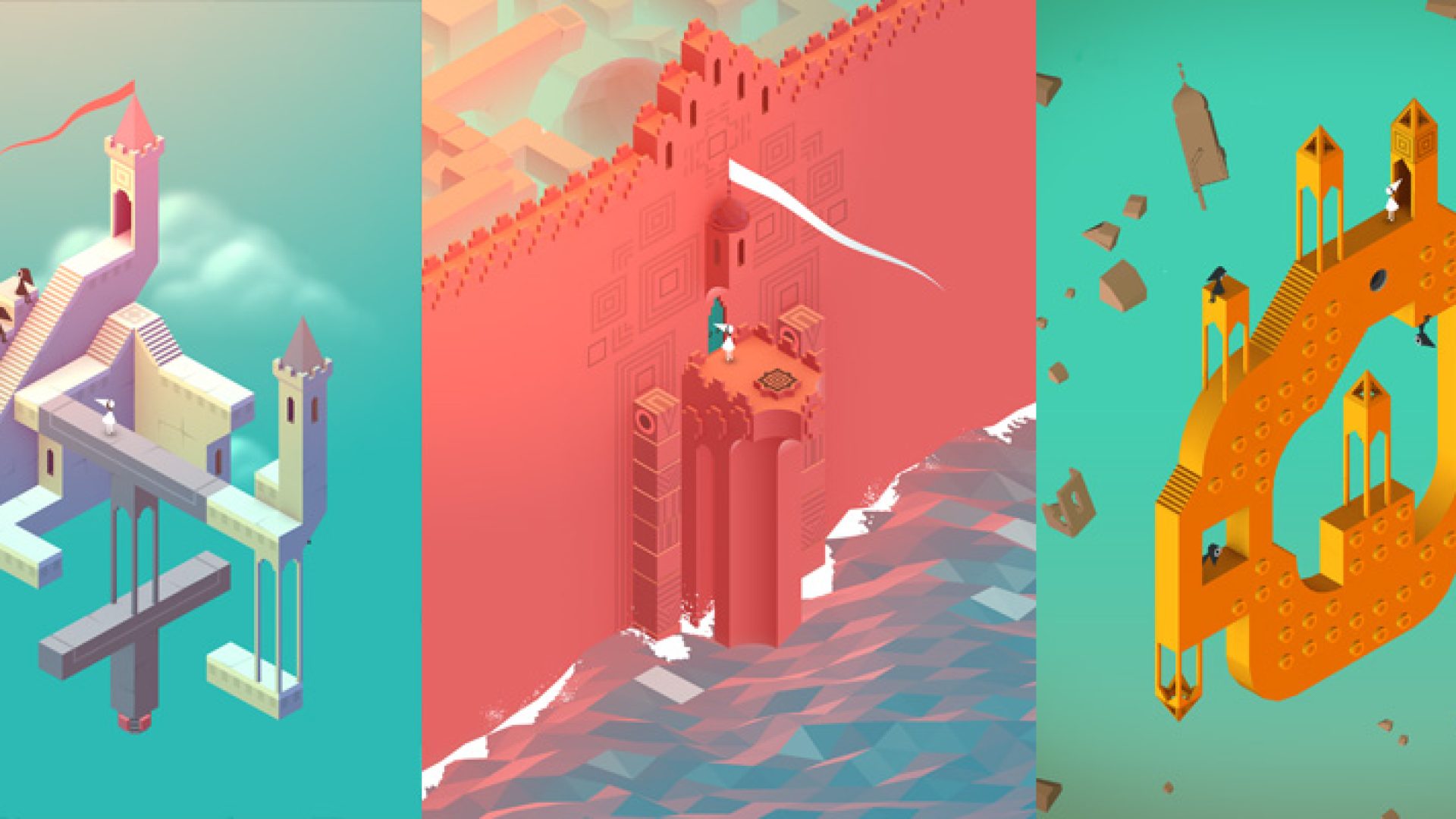

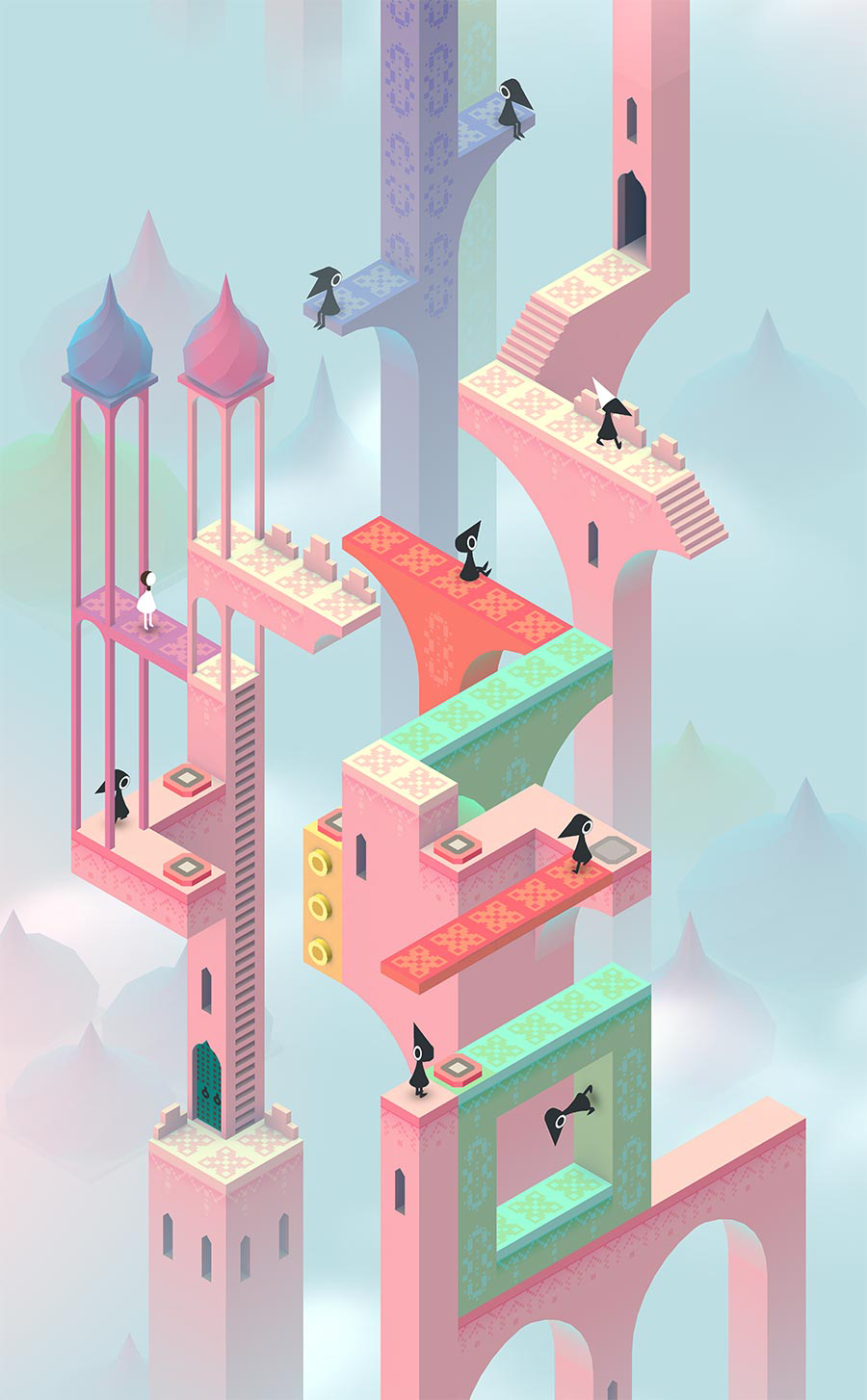

The media used to transmit these peculiar ideas should be therefore mutated and tuned according to people’s desires to captivate them and challenge their views. Monument Valley, for instance, is a video game whose settings will instantly teleport the players inside one of Escher’s etchings or Aldo Rossi’s drawings. The aim of the game is fairly simple, but its graphic has a complexity and an idyll which makes people wonder what it would mean to live in an environment where the interaction with architecture would radically change according to the perspective we are looking at.

This exquisitely designed video game, with 500,000 copies sold in the first month of its debut, has seen a fame and favorable reception that New Babylon or Plan Voisin today, could not have achieved. Somehow, Monument Valley was able to share Escher’s view to people more effectively than the artist himself. Amongst our society, video games are a highly consumed commodity, and using them as a canvas to tell stories about conceptual architecture will grant the attention of a larger audience.

Beyond digitising a utopistic idea, inserting its principles and concepts within everyday life activities like playing a video game on our mobile phones signifies making it interactive, responsive, and accessible, finely fulfilling the aim of speculative architecture.

Is this not the way speculative design should operate? Finding new paths to open up to a larger cohort and challenge our ideas of reality? The rules that make video games, like other technological media, are pliable, unlike the rules that make our infrastructure; switching the planes on which we have been speculating in order to become more appealing should be essential to move forward.

Making this discipline relevant to the current environment we inhabit should be the motor to legitimize it within the practice of architecture. Liam Young is a speculative designer that has been working towards this objective. Creator of a master program named Fiction and Entertainment at the Sci-Arc architecture school in Los Angeles, he believes in the importance of forging stories in architecture and not only creating buildings; the constant inputs we receive, from new technologies to remarkable political changes need to be addressed re-imagining where new forms of agency could exist in the urban fabric.

“Where the City Can’t See ” is the title of one of Young’s works, a short movie exploring the possibilities of cities at the mercy of an all-seeing technology. The only “safe” or “unseen” areas become the left-over and shadowy places, the cracks. Not controlled by technology, they become the new areas where people can evade their realities. Through his work, Young is proposing a scenario where architecture and our society could fall into and, through the medium of cinematography and rendering, he is reaching to a broader public through appealing graphics. His work is relevant, it is not engaging only architects but people from different fields. As a result, his work aids in broadening the knowledge and acceptance of Speculative design, hence legitimising this discipline.

Paradoxically, we are surrounded by utopistic and speculative graphics, from Miyazaki’s movies to video games like Manifold Gardens and the majority of these ideal realms do not involve the canonical tools employed to depict Speculative architecture in the past. The combination of contemporary media, cutting-edge ideas, and pioneering intentions means more people becoming interested in the potential of speculating about urbanism. Though it may seem contradictory, this conceptual architecture finds a place in our world through these unexpected media and it is through them that it should evolve and develop in order to find its own parameters, detached from the physical architecture.